The African American Performer on the San Francisco Stage

Within the history of the black performing artist lies the story of a nation’s struggle to establish a multicultural society. African rhythms survived the journey to America in the seventeenth century and surfaced in mainstream popular culture hundreds of years later. The black minstrels of the nineteenth century, although narrowly restricted to portraying degrading stereotypes developed by white minstrels, were the first to infuse a popular American entertainment form with black culture.

The path these first African Americans forged illuminated the way for the future wave of black musicians, singers, and dancers to smash even greater barriers, such as “legitimate theater” and ultimately, Broadway. As a result, African American dance and music was introduced to the American public on a grand scale and the rhythms of ragtime, boogie woogie, jazz dance and music swept the nation. Today, it is impossible to study the American cultural experience without considering the enormous contribution of the black performer.

San Francisco permitted more freedom in the nineteenth century than most other American cities. Although racism and discrimination were still a major reality for the African American performer in the Bay Area, there existed an atmosphere of opportunity and freedom that was rarely experienced elsewhere. This is, by no means, the complete story, but a starting place for probing some of the lesser known layers of America’s intricate history. — Dr. Patty Yancey

Callender’s Minstrels

The Gold Rush brought the minstrel show to California in 1849. It became the most popular form of entertainment in America until the turn of the century. First performed by white men in blackface makeup, minstrel shows had songs, dances, jokes, and skits.

The minstrels used what they claimed were Southern Negro dialects and portrayed “authentic” life on the plantation. The first recorded all black troupes were “The Mocking Bird Minstrels” appearing on the stage in Philadelphia in 1855 and the “genuine Negro Minstrels” performing at the Red Onion Opera House in San Francisco around the same time.

After the Civil War (1861-1865), more African Americans began performing to both white and black audiences on the stage and eventually became the stars of the minstrel shows. However, they still conformed to the tradition established by white minstrel performers of wearing blackface makeup.

At this time, minstrelsy was the only public performing art form, other than church-sponsored recitals and the celebrated black college choruses, open to African American singers, dancers, and actors

Callender’s Minstrels

Oscar Jackson

Oscar Thomas “O.T.” Jackson (1846-1909), a tenor singing with local minstrel groups in the Watsonville-Santa Cruz area, moved to Oakland in 1874 and soon after broke into the “big time” when he joined Haverly’s Colored Minstrel Troupe. He later signed on with Charles Hick’s Georgia Minstrels — the first black managed company — and toured the world for almost six years culminating with a command performance before King Edward VII in London in 1883.

After another two-year performance tour to Australia and England with Hick’s troupe in 1886 and a stint playing “secondary markets” across the U.S. with other lesser known minstrel groups, Oscar Jackson retired from the stage and in 1898 resumed his previous profession as a barber in Oakland.

Oscar Jackson

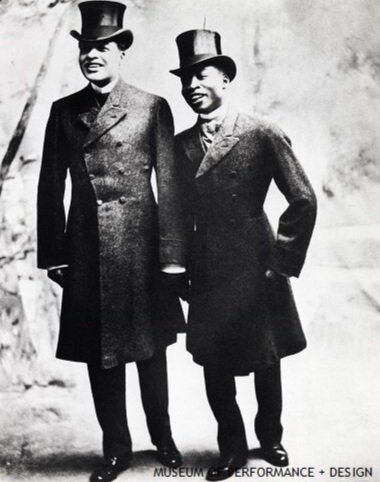

Williams and Walker

Bert Williams (1874-1922) and George Walker (1873-1911) met on San Francisco’s Market Street in 1893 and soon after began their career together in the 10-man integrated troupe of Martin and Seig’s Mastodon Minstrels. The two talented performers worked hard to develop their own musical-comedy variety act without the stereotypical blackface makeup, but found it difficult to become a hit with white audiences without the minstrel props and mannerisms.

They eventually incorporated the minstrel dialect and blackface makeup into their act and persevered to become the most popular African American musical-comedy duo in the nation at the turn of the century. The quality of their work shone through the stereotypical facade they had to adopt and paved the way for other African American singers and dancers to break out of minstrelsy into other performing art forms on the American stage.

Bert Williams and George Walker

Bert Williams

Bert Williams (1874-1922) of the Williams and Walker duo went on to greater fame as a solo comedian and singer. The first African American to attend Stanford University, Williams, a naturally reserved gentleman, found it distasteful to wear the blackface makeup of the minstrel, but eventually conformed to tradition to please audiences.

He discovered, to his surprise, that the minstrel mask liberated his sense of humor and allowed him to become a different person on stage. In 1910, he became the first African American actor to perform in the Ziegfeld Follies, a famous Broadway musical revue.

He performed on stage with many of the most famous white comedians of the era, such as W.C. Fields and Eddie Cantor, and is considered the first black superstar in the history of the American theater. Unfortunately, Williams was never able to discard the blackface minstrel stereotype onstage, and it eventually eroded his self-image and dignity as a man.

Bert Williams

Ada Overton Walker and George Walker

Ada Overton Walker (1880-1914) was an accomplished dancer by the age of sixteen and became a star of the stage when she joined the Williams and Walker company. She and George Walker, famous for their version of the cakewalk dance, married in New York City in 1899. In 1909, when George became to ill to work, Ada impersonated him on stage and performed his theme song in the Williams and Walker production, Bandana Land.

Drawing of Ada Overton Walker

Al & Mamie Anderson

Al and Mamie Anderson, another famous husband and wife team known for their dancing and comedy act, were a hit at the Orpheum in downtown San Francisco in the late 1890s and early 1900s. The Andersons were among the first African Americans who did not start out in show business as minstrels. They performed in a new style of musical-comedy entertainment sweeping the nation — vaudeville.

Al and Mamie Anderson

Sissieretta Jones

Sissieretta Jones (1868-1933), also known by her stage name “Black Patti,” was one of vaudeville’s first, nationally acclaimed African American female stars. Because of her beautiful, operatic singing voice, the press nicknamed her “Black Patti” after a famous white opera star, Adelina Patti, who was internationally famous around the same time.

Ms. Jones performed at the White House three times for three different presidents during her illustrious career. In the early 1900s, she toured in over 2400 shows across the United States, accompanied by her talented group of African American singers, dancers, musicians, and comedians. San Francisco was a favorite stop on the tour, with sold-out crowds packing the Orpheum every night to cheer the troupe. Eubie Blake and Josephine Baker were among the popular performers that began their careers in “Black Patti’s Troubadors.”

Sissieretta Jones

Bunny Hug

Before World War I, African American popular dances swept the country and became national dance crazes. Some of the most famous dances — the Chicken Glide, the Turkey Trot, the Grizzly Bear, and the Bunny Hug — were first performed in the dance halls of the Barbary Coast.

Bunny Hug

Keeton Chorus

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, President Roosevelt established the Federal Theater, Music and Dance Project (FTP) under the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to give work to unemployed artists.

FTP presented many African Americans with their first opportunity for professional training in technical theatre, design and stage management. As a result, the San Francisco Bay Area became known for African American theater. One of the most successful of the local FTP theatrical companies was the Keeton Chorus, founded by Oakland resident W. Elmer Keeton.

Keeton Chorus

Ethel Terrel

Ethel Terrel, pianist-leader of a vaudeville band and former member of Black Patti’s Troubadors, travelled to San Francisco in the 1920s to perform at the Orpheum and later decided to settle permanently in the East Bay. In the 1930s, she supervised a WPA theatre group in the successful black musical Change Your Luck.

Ethel Terrel

Freddie McWilliams

Freddie McWilliams, a Bay Area resident, was well-known in the local 1930s show business circuit as a tap dancer and master of ceremonies. From 1933-1936, he toured the Far East with Change Your Luck.

Freddie McWilliams

Calvin Simmons

Born in San Francisco in 1950, Calvin Simmons (1950-1982) was a child prodigy and began his musical career at the age of nine with the San Francisco Boy’s Chorus. He went on to become one of the outstanding conductors of his generation, conducting the San Francisco, Los Angeles, Houston, and New York Symphonies, the San Francisco Opera, New York’s Metropolitan Opera, and England’s prestigious Glyndebourne Opera.

In 1979, he became Music Director and Conductor of the Oakland Symphony. His brilliant career was cut short at the age of 32 when he drowned in a canoe accident in 1982. The Calvin Simmons Theater and the Calvin Simmons Middle School in Oakland are named in his honor.

Calvin Simmons

This online exhibition features text by Dr. Patty Yancey and is based on an educational show written by Dr. Yancey for the Museum of Performance + Design under its previous name, San Francisco Performing Arts Library & Museum.

The exhibition is supported in part by a grant from Grants for the Arts.